Word processing did not develop out of computer technology. It evolved from the needs of writers rather than those of mathematicians, only later merging with the computer field. The history of word processing is the story of the gradual automation of the physical aspects of writing and editing, and the refinement of the technology to make it available to individual and corporate users.

GOING BACK TO GUTENBERG

Even in this brief history of word processing, it’s helpful to momentarily go back a few centuries to when Johannes Gutenberg in 1439 invented moveable type.

Before Gutenberg, all books were completely handwritten. There was no printing as we know it today. Making a second copy of a book involved hiring a scribe to copy the entire book again by hand. Gutenberg essentially invented the printing industry by replacing handwritten letters with blocks of type. Setting the type was laborious, but once it was done the pages could be reproduced much faster, cheaper and in much larger quantities. A Bible Gutenberg completed in 1455 cost the equivalent of three years’ wages of the average clerk—expensive, but a fraction of the cost of hiring a scribe. Books and pamphlets began to fly off the presses, helping to usher in the Reformation, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment or really the world as we know it today.

Still, someone had to write the text in the first place which required putting pen or pencil to paper. It took more than four centuries for that to change, but eventually it did with the development in the late 1800s of the first successful typewriters. The invention of printing and moveable type at the end of the Middle Ages was the initial step in this automation. But the first major advance from manual writing as far as the individual was concerned was the typewriter. Henry Mill, an English engineer of the early eighteenth century, is credited with its invention. The fact that almost nothing is known about his early version today is evidence of its lack of success.

The invention of the typewriter

Christopher Latham Sholes, with the assistance of two colleagues, invented the first successful manual typewriter in 1867. It began to be marketed commercially in 1874, rather improbably by a gun manufacturing company, E. Remington and Sons. The main drawback of this model was that it printed on the underside of the roller, so that the typist could not view his work until he had finished.

Acceptance of the typewriter was slow at first but was facilitated over the next several years by various improvements. These included: the shift key, which made it possible to type both capital and lower-case letters with the same keys (1878); printing on the upper side of the roller (1880); and the tab key, permitting the setting of margins (1897).

Eventually, at first in the corporate sector, the typewriter began to catch on. Businesses, which had their records and correspondence written and copied by hand, found their paperwork could be done more quickly and legibly on the typewriter. Typewriting was put within the reach of individuals by the development of portable models, first marketed in the early 1900s.

Thomas Edison patented an electric typewriter in 1872, but the first workable model was not introduced until the 1920s. In the 1930s IBM introduced a more refined version, the IBM Electromatic. It "greatly increased typing speeds and quickly gained wide acceptance in the business community."

This was soon followed by the M. Shultz Company's introduction of the automatic or repetitive typewriter, perhaps the greatest step from the typewriter towards modern word processing. The Shultz machine's main innovation was automatic storage of information for later retrieval. It was a sort of "player typewriter," punch-coding text onto paper rolls similar to those used in player pianos, which could later be used to activate the keys of the typewriter in the same order as the initial typing. With the automatic typewriter, it was possible to produce multiple typed copies of form letters identical in appearance to the hand-typed original, without the intermediary of carbons, photocopiers or typesetting.

The bulky paper roll machine was succeeded by a device called the Flexowriter, which used paper tape. This had a key that allowed the deletion of mistakes from the tape and copies by punching a "non-print" code over the code for the character erroneously typed. Long passages of text could be deleted or moved by literally cutting the tape and pasting it back together.

TYPEWRITERS IN THE 1960’S

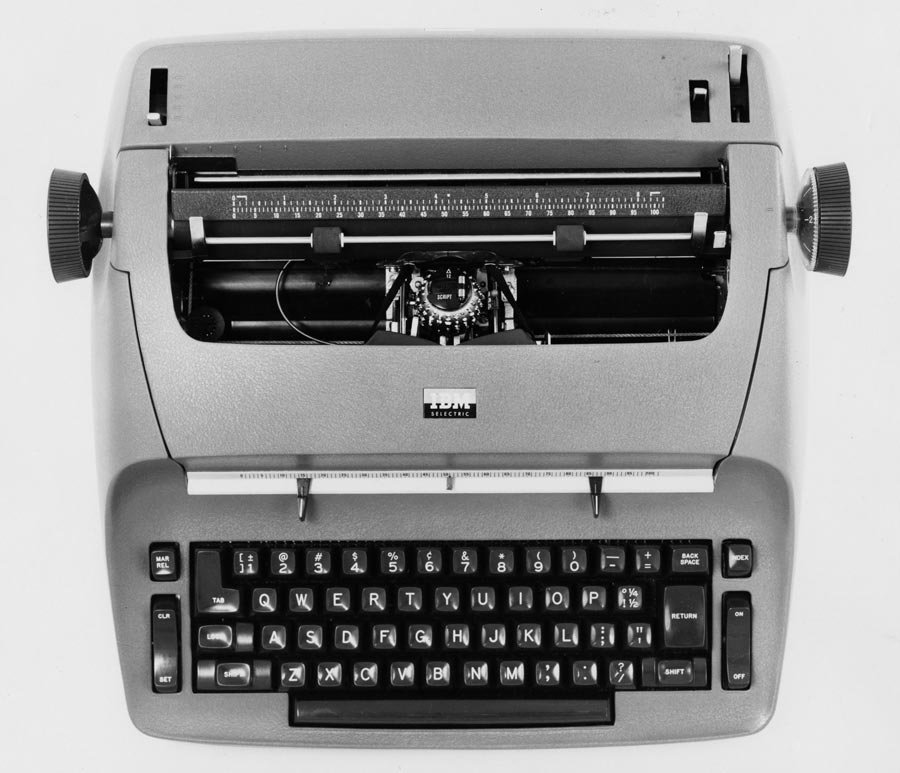

In 1961 IBM introduced the Selectric typewriter, which replaced the standard movable carriage and individual typestrikers with a revolving typeball (often referred to as a "golfball" or "walnut"). This could print faster than the traditional typewriter.

In 1964 IBM brought out the MT/ST (Magnetic Tape/Selectric Typewriter), which combined the features of the Selectric with a magnetic tape drive. Magnetic tape was the first reusable storage medium for typed information. With this, for the first time, typed material could be edited without having to retype the whole text or chop up a coded copy. On the tape, information could be stored, replayed (that is, retyped automatically from the stored information), corrected, reprinted as many times as needed, and then erased and reused for other projects. This development marked the beginning of word processing as it is known today.

It also introduced word processing as a definite idea and concept. The term was first used in IBM's marketing of the MT/ST as a "word processing" machine. It was a translation of the German word textverabeitung, coined in the late 1950s by Ulrich Steinhilper, an IBM engineer. He used it as a more precise term for what was done by the act of typing. IBM redefined it "to describe electronic ways of handling a standard set of office activities — composing, revising, printing, and filing written documents."

Since the invention of the MT/ST, advances in technology have made word processing systems less expensive to produce, leading to intensified competition among developers and an increase in the development rate of new packages.

In 1969 IBM introduced MagCards, magnetic cards that were slipped into a box attached to the typewriter and recorded text as it was typed on paper. The cards could then be used to recall and reprint text. These were useful mostly to companies which sent out large numbers of form letters. However, only about one page-worth of text could be stored on each card.

WORD PROCESSING

In 1972 Lexitron and Linolex developed a similar word processing system but included video display screens and tape cassettes for storage. With the screen, text could be entered and corrected without having to produce a hard copy. Printing could be delayed until the writer was satisfied with the material.

The floppy disk marked a new stage in the evolution of storage media. Developed by IBM in the early 1970s for use in data processing (that is, traditional number computation), it was soon adopted by the word processing industry. Vydec, in 1973, seems to have been the first manufacturer to produce a word processing system using floppy disks for storage. Previous storage media could only hold one or two pages of text, but the early disks were capable of holding 80 to 100 pages. This increased storage capacity permitted the creation and easy editing of multipage documents without the necessity of changing storage receptacles.

Floppy disks could also be used to hold programs. The most important advance in word processing was the change from "hard wired" instructions built into the machinery to software on disks. When the programs were part of the equipment, they were difficult to change and expensive to upgrade. Programs on disks could be updated more economically, since a rewritten program could be loaded into and used with the same hardware as the old one.

Before disk programs most word processing packages were "dedicated" systems, which were bulky and expensive, and did not admit computing functions other than word processing. Disk programs made it practical to develop packages for use with personal computers, first made available in completely assembled form in 1977. Thus, the separation of the software from the hardware also opened up the field to individuals. Word processing is now "one of the most common general applications for personal computers."

Over the next ten years many new features were introduced in the field. One important innovation was the development of spelling check and mailing list programs. Another advancement, introduced by Xerox in its Star Information System, allowed working on more than one document at a time on the same screen. Some programs now even incorporate bookkeeping and inventory functions, combining word processing with data processing and completing the marriage of the word processor to the computer. The combined field is known as information processing.

THE RISE OF WORD PROCESSING

In the 1970s, the invention of larger storage devices (the first floppy disks) and cheaper computer memory led to word processing solutions capable of storing and managing whole documents. That was followed by the addition of cathode ray tube (CRT) screens and computerized printers. Now you could easily view the entire page as you were typing, go back and forth to make edits and instantly print out the results. The modern era of word processing took off.

At first, there was a boom in dedicated word processors, which are essentially computers with proprietary software whose sole function was to churn out typed documents. Companies who made them, such as Vydec and Wang Laboratories, became hugely successful. Individuals still used typewriters, but dedicated word processors took over for large offices and large-scale document production.

Then came the PC revolution starting with Apple in 1977 and then the IBM PC in 1981. Word processing quickly became one of the most popular applications for these new devices with programs such as WordStar, WordPerfect, MultiMate and Microsoft Word in hot demand (the first version of Microsoft Word appeared on its own in 1983 and later became part of Microsoft Word Office). These programs were not cheap—sometimes $500 and up. There were endless debates over which was the best word processor, but each one made it possible to duplicate many (if not all) of the functions of a dedicated word processor.

Just as Gutenberg revolutionized printing, and the typewriter revolutionized the production of business documents, the PC revolutionized word processing. Now for the price of the software and a thousand dollars plus for the PC, you could avoid spending tens of thousands of dollars on a dedicated word processing solution. The market for dedicated word processors plummeted and the history of the word processor as it had been known was essentially over. PCs began to replace typewriters and word processors in offices throughout the world.

What’s been lost in the history of word processing

Still, in the evolution from typewriting to word processing (and now in the era of the cloud-based online word processor), something has been lost. And it’s not insignificant.

Typewriters were so limited in their formatting capabilities that, everyone learned how to format them the same way. So, inevitably, one business letter looked very much like any other business letter.

Today, just the opposite is the case. With a program like Word, you can create any look you want. That’s, of course, good and bad—and it can be really bad if you care about the image and the brand you are conveying with your business documents.

In many businesses today, failure to follow basic formatting and templating leads to “document anarchy”: business documents produced using different fonts, different logos, different colors. The visual clues that help tell the recipient who the document is from and what it’s about—clues that are essential to fast, accurate communication—get lost entirely.

THE PC REVOLUTION

When personal computers, printers, and computer applications for word processing came onto the scene, sales of dedicated word processor machines plummeted. In 2009, there were just two American companies – AlphaSmart and Classic – which continued making them.

Early word-processing software required users to memorize semi-mnemonic key combinations rather than pressing keys labelled "copy" or "bold". (In fact, many early PCs lacked cursor keys; WordStar famously used the E-S-D-X-centered "diamond" for cursor navigation, and modern vi-like editors encourage use of hjkl for navigation.) However, the price differences between dedicated word processors and general-purpose PCs, and the value added to the latter by software such as VisiCalc, were so compelling that personal computers and word processing software soon became serious competition for the dedicated machines.

The late 1980s saw the beginning of laser printers, a "typographic" approach to word processing (WYSIWYG - What You See Is What You Get), using bitmap displays with multiple fonts (pioneered by the Xerox Alto computer and Bravo word processing program), and graphical user interfaces (another Xerox PARC innovation, with the Gypsy word processor). These were popularized by MacWrite on the Apple Macintosh in 1983, and Microsoft Word on the IBM PC in 1984; these were probably the first true WYSIWYG word processors to become known to many people. Dedicated word processors became museum pieces.

Of particular interest to many is the standardization of Truetype fonts used in both Macintosh and Windows PCs. While the publishers of the operating systems provide Truetype typefaces, they are largely gathered from traditional typefaces converted by smaller font publishing houses to replicate "revered" fonts. Advertising continues to create a demand for new and interesting fonts, which can be found free of copyright restrictions, or commissioned from font designers. "Software With Flair" was a software house, as an example, that employed artists in the 1980s and 1990s to create fonts.

Today, typical word processing software comprises more than one program and can produce a combination of graphics, images, and text – with the text having type-setting capability.

Most programs on the market today have:

Multiple font sets

Grammar checking

Thesaurus

Spell checking

Automatic text corrector.

HTML conversion.

Web integration.

Pre-formatted layouts for newsletters, to-do lists, etc.

Where are word processors used?

In the world of business, word processors are extremely common. They are used for creating legal documents such contracts, company reports, literature for customers and clients, internal memos, and letters.

Most companies have their own format and style, and either have the company letterhead programmed into the word processor software, pre-printed on paper, or both.

In people’s households, word processors are used for business, educational, and planning purposes.

Some people use the software to write poems, short stories, personal correspondence, greeting cars, or to create résumés (CVs).

Since the advent of social networks and email, the role of the word processor in the home has declined considerably. What used to be done in printed form (on physical paper), is now done almost entirely online.

The top word processors (software) in the world are:

Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation – United States)

Word Perfect (Corel Corporation – Canada)

TextMaker (SoftMaker Software GmbH – Germany)

Google Docs (Google Inc. – United States))

Kingsoft Writer (Kingsoft 金山软件有限公司 – China))

Ability Write (Ability Software International – United Kingdom)

RagTime ((RagTime.de Development GmbH – Germany)

The IDEA Club

CRAIG REAHL

KITTINGER BUSINESS MACHINES

Kittinger business Machines offers a complete line of digital office solutions, your one-stop-shop for everything your office needs in office equipment.